Now that most of the dust has settled, I’ve decided to sit down and write about my views on the recent death of Osama bin Laden. Just in case my lone reader lives in a cave and hasn’t heard the news, here’s a quick recap of the situation: On May 2nd, U.S. forces entered a compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, and killed Osama bin Laden, head of al-Qaeda and presumed mastermind behind various terrorist attacks against several nations over the past two decades.

I’ve had many arguments over the legality and ethics of the action over the past several weeks, and I’m pretty sure they all ended with all the participants maintaining the same positions they had at the beginning. I’ve read several articles with opposing views discussing the situation, by Chomsky, Hitchens, Moore, and many others. It seems to me that the main disagreement is over unstated basic assumptions and prejudices, and since it is almost impossible to convince others that your own basic assumptions are correct and theirs are not, these arguments cannot move forward at all.

Therefore, I will attempt to be as explicit as possible with my basic assumptions, and try to draw conclusions from those. Moreover, I will attempt to be reserved enough when drawing conclusions that any disagreement with the conclusions must be directly traced to a disagreement over the basic assumptions. This may be tedious to read (and write), but I feel like I need to do it so that I can stop twisting my head around the issue. Here are the assumptions:

- If it is ethical to do something once, it is always ethical to do it. Moreover, if it is ethical for me to do something, it is also ethical for anyone else in my same situation to do it. I hope most people would agree with this, but I recognise that there are infinitely many conceptions of ethics and there will always be people with different points of view. If you are such a person, you can stop reading now, the rest of the argument will certainly not convince you.

- Osama Bin Laden, as head of al-Qaeda, was the mastermind, or at least the one who gave the executive orders behind all terrorist attacks that have been attributed to his organisation. This includes, but is not limited to, the attack on the World Trade Center of September 11, 2001. Some people may still consider this claim controversial, but let us assume it is true for the sake of argument.

- The September 11 attacks were unethical because they were aimed at innocent civilians, who had nothing to do with whatever bin Laden was fighting against. Once again, this could be argued against since the U.S. is a democracy and each voting citizen is in some way responsible for the actions of their government, but recall that children also died in the attacks and surely children cannot be held responsible for the actions of any adult.

- Since bin Laden was in hiding and willing to resist an arrest, it would have been impossible to try him for his crimes before any kind of court. Again, this is disputable, and we will probably never know if it would have been possible for the U.S. marines involved to capture him alive, but let us assume this is true.

If from assumptions 2-4 it follows that it was ethical for the U.S. government to send in its marines and kill bin Laden, from Assumption 1 it follows than if 2-4 ever apply in any other case, it would be ethical for a different government to do the same. Now consider the following claims:

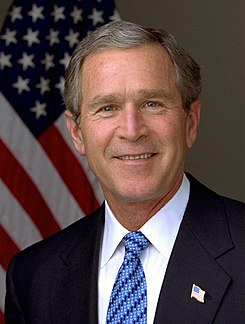

- George W. Bush, as president of the United States, gave the executive order to invade both Afghanistan and Iraq. I doubt anybody could deny this.

- Thousands of civilians have died in both of these wars, in fact more than the total number of civilian casualties of al-Qaeda attacks combined, but let us not worry about numbers. The point is that innocent civilians which had absolutely nothing to do with any atrocities that may have been committed by their leaders (as they did not have the right to vote) died as a direct cause of these wars.

- It is practically impossible to take a former U.S. president to court because of war crimes committed during their term. I do not think that has ever happened before, though several U.S. presidents have certainly been responsible for all kinds of atrocities (cf. Reagan). In fact, when a human rights group in Switzerland tried to sue Bush for acts of torture in Guantanamo, he simply cancelled his trip. There is a possibility that one day a U.S. president will be brought to trial, but I think it is hard to imagine a future in which George W. Bush is facing a court for any crime committed while he was in office.

- The invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan were done in self-defence, while bin Laden’s attacks were unprovoked.

- The casualties of war were collateral damage, civilian casualties were never the aim and were in fact actively avoided.

- When the U.S. attacks countries, it does so to expand democracy. When bin Laden does it, he does it to create an Islamic caliphate. The second aim is in some way less legitimate than the first.

Against Objection 1 I can say what I said earlier: clearly the civilians that suffered from these wars were not the ones that provoked the attack, and therefore it is unjust that they should be punished for crimes they did not commit.

Objection 2 is a bit more difficult to deal with. However, we must realise that for the victims it does not matter whether the bombs that fell on their homes were meant to fall there or elsewhere. If on reading bin Laden’s diaries we were to realise that the planes were not meant to fall on the W.T.C. but on the U.N. headquarters, would the victims of the attacks be happy with it and immediately forgive him? I highly doubt it. Now let us imagine a government formed entirely by the victims of, say, the Iraq invasion, a country in which every citizen lost at least one friend or family member to a stray U.S. bomb during the war. Let us call this country Iraq 2. To the citizens of Iraq 2, clearly George W. Bush would be a murderer regardless of his intentions, and so they would be interested in trying him, but because of Claim 3, they would not be able to.

This also deals with Objection 3, since the people of Iraq 2, as we have said, do not care about intentions; one may say they have become strict Utilitarians because of what they’ve suffered. Besides that, this objection is clearly a direct product of propaganda, completely blind to basically all of the history of the 20th century.

It follows from the above that, since George W. Bush is clearly a criminal to all of these people, and it would be impossible to bring him to trial, and any attempt by the special forces of Iraq 2 to break into his mansion in the middle of the night and take him to an international court will certainly be met with armed resistance, if not from the U.S. military at least from Bush’s bodyguards, then by our initial assumptions it would be ethical for the president of Iraq 2 to send a mission to “kill or capture” Bush.

However, since this would seem to be a bad thing, or at least since I don’t think it would be a good thing for anybody to kill Bush, much as I may dislike him (if you would consider it a good thing then you can stop reading, I won’t be able to convince you of anything), it appears that our conclusion is wrong. But if it is ethical to kill Osama and not Bush, we would be violating Assumption 1, on which the argument was based. Therefore it was also unethical to kill Osama.

I realise that bin Laden’s acts had a deep emotional effect on many people, and that it is almost impossible for the same people not to have emotional reactions to his death. I am not saying that if I were in the same situation, if I had for example lost a friend in one of his attacks, I would not be happy about his death. I am human too, and I do not think there is any human that has not, at some point in their lives, wished for the death of another human. But we must distinguish between emotion and reason, and, if my argument is correct, no matter how good it makes anyone feel, killing Osama bin Laden was wrong.

Edit: Here is a more thorough post by Chomsky.